" A great boon to ancestor-chasers in the Ewes Valley". Douglas Elliot of Burnfoot of Ewes expresses the feelings of many, most eruditely, when he writes, "Over the years , many families have come to the Parish, some stayed, many are spread throughout the land, others moved to far-flung corners of the world, but to any who are drawn back in body or imagination to the watergate of Ewes, the following pages will be of interest and a guide to all, old or young, at home and abroad"

***************************************** EWES VALLEY By JOHN ELLIOT, LANGHOLM

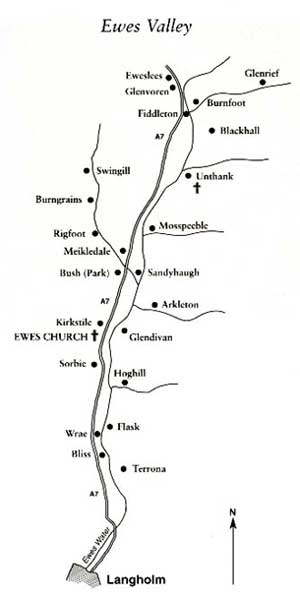

Each valley and watergate in this Borderland of ours has its own peculiar story and that of Ewes is well worth talking over. What can I say about Ewes except that it is on the road to Hawick? That may be so, but what stories were told of that same road in bygone times. Could I but conjure back to consciousness the men - drivers of the mail coaches, men like Sandie Elder of the Cross Keys, and old Govenlock of Mosspaul, or some of the carters and carriers of 100 years ago who travelled that road to Hawick - their tales would keep you interested all night, talks of robberies, accidents, hairbreadth escapes and adventures - adventures in coming down from Mosspaul when the drifting snow was blowing up the burn. Or could I recall to you the gossip collected by Tom Robson, the post runner, who “ran” with the letters from the Langholm and fished all the way up the Ewes - or of his successor, Willie Beattie, who was nearly done to death by highwaymen in the Wrae Wood, and later was accidentally shot while cleaning the pistol he carried for his own protection - then we would all realise that this same watergate of Ewes was alive with a human as well as a historic interest. I have often applied to our watergate, too, what the poet said of Killarney: “Angels often pausing there doubt if Eden were more fair,” for indeed on a summer morning the valley of Ewes is surpassing fair. It was perhaps this idea of Eden, or Paradise, that was in the mind of auld Chairlie Hope, one of the characters in Langholm just over 100 years ago. Chairlie’s people were buried in Staplegordon and he imagined he had some grievance against a well-known family in Langholm for encroaching upon his grave space. He made the whole town ring with his tale of ill-treatment. One day, however, someone saw Chairlie at Staplegordon, building an archway in the stone dyke over the head of his wife’s grave, and inquired what he was doing. “Oh well,” said Chairlie, “it’s for use on the Resurrection morning, for the others’ll be oot an’ through Sorbie Hass afore the wife can climb the dyke.” Evidently Chairlie thought the golden city with its streets so fair lay at the Ewes end of the Hassó surely a high compliment to the watergate of Ewes. EWES AND LANGHOLM But though the Ewes valley may be the road from Langholm to Hawick it has nevertheless an individuality of its own and a place in history that is independent of its neighbours. Langholm, for example, is only some 350 years of age. It was in 1621 that Maxwell received the Charter giving him the lands of Langholm and other places, and in 1628 the building of the town was begun. But Ewesdale, as a geographical division, has been known to history for 500 years and more. So that historically it is Langholm we have to relate to Ewes and not Ewes to Langholm. Indeed in Molls Map of 1745 Eskdale is not separately mentioned - the whole watershed is called Euesdaill. The lands of Langholm formed part of the Regality of Eskdale which included the Baronies of Staplegordon, Langholm, Westerkirk, Canonbie, Tarras and the Tenandrie of Dumfedling. But Ewes, more definitely to the north of Arkin, was no part of these nor does there appear to have been a Barony of Ewes in the same sense as these other places. Indeed, Maxwell, who was Warden of the Marches, denied that Ewes came under his jurisdiction. The lands in the watergate were granted by charter from time to time but there was no Baronial holding. This is a very important distinction and, it partly explains the present day feature of separate lairdships of Meikledale and Arkleton. Perhaps the difference may be expressed in this way - that whilst Eskdale was feudal, Ewes was more under the rule of the Clan. Though there was no absolute baronial rule, there was an approach to it in the Tenandrie of Glenvorane corresponding to that of Dumfedling in Eskdale - where justice would be dispensed. There was one fundamental difference, however, between Tweeddale and Eskdale: that of the jurisdiction of the superior. Under the Baronies, the superior had the right of pit and gallows, but no such power seems to have existed in Ewesdale, because in none of the Charters relating to Ewes of the sixteenth century is there conferred the power of life and death. CORN MILLS There was another important difference between Ewesdale and Eskdale in the corn mills granted under the Charters. In the nine or ten miles from Langholm to the entrance to Mosspaul Burn there were mills at no fewer than six houses: Meikledale, Sorbie, Arkleton, Bliss, Glenvorane, and Wrae. These have been not in any appear to different from the mills in Eskdale area in that they were sense baronial mills to which the cultivators were “thirled.” Thirlage was one of the most objectionable and irritating feudal customs. It caused every farmer and every cultivator of the soil to regard the miller as his natural enemy. Oppression and favouritism were common and the miller had a hold over every cultivator and had the sanction and authority of the feudal lord behind him. Obviously with six mills in so limited an area no miller practised exactions such as were customary both as to charges and what were known as “multures” or “sequels.” According to the late Mr Robert Hyslop, joint author of “Langholm As It Was,” we have an excellent illustration of sequels in the Barley Bannock and the Salted Herring carried as emblems in the Common Riding procession. The miller, and later, the baron-bailie had the right to these sequels and the giving of these was resented by the tenants. The Baronial Mill of Staplegordon was at Milnholm, and of Langholm at the Milltown at the foot of the Chapel Path. SHIRES At one time both Eusdale and Eskdale were within the Shire of Roxburgh - so says a Charter dated 1458 - but it is supposed that this is one of these misprints one sometimes finds in documents written at a considerable distance from the place, for only a few years later they are ascribed to Dumfries and continue so down through the 16th century. In 1672, however, the Duke and Duchess of Buccleuch petitioned Parliament to have the five Eskdale parishes transferred to the County of Roxburgh for convenience of administration and this was granted. In Molls Map of 1745 both Ewes and Eskdale are shown as being in the County of Roxburgh, but only two years later, on the passing of the Heritable Jurisdiction Act in 1747 - an Act to rearrange and define the rights and privileges of the feudal superiors - the parishes were again restored to Dumfries. Had not this been done, I suppose we might easily have been described as Hawick folk. But not only is Ewes separate and distinct in a geographical sense, but it has history and characteristics not shared by its neighbours. RELICS The oldest relic in the watergate, I suppose, is one which takes us back to before the period of written history, and is the stone known as the “Grey Wether,” standing in front of Meikledale House. Such stones are found here and there over Scotland and England, and in Scotland, at any rate, they are all known as “Wethers” - a derivation and meaning at which it is difficult to arrive. Some suppose they mark the burial place of some famous chief - others aver that they were objects of worship - but it is difficult to say. Then one might mention the Turf Dyke running athwart the hills on the left bank of the Ewes an antiquity which interested so keenly the late Mr Matthew Welsh. Its purpose is one of those debatable themes, of which archaeology provides so many, but its similarity to the famous Catrail suggests a similar purpose. Mention might be made also of the old British Camps scattered about the watergate - at Footsburn, Arkleton, Meikledale, Unthank and other places in Ewes. There is one singularity of Ewes which is rather puzzling, and that is that in the charters conveying lands in Eskdale and Wauchopedale there should so often be expressly reserved to the superior “the salmon and other fisheries of the Esk and Wauchope” - Ewes being left unmentioned. There is only one charter in which the fisheries of Ewes are included - that of 1621 to the Earl of Nithsdale. Perhaps the reason lies in the fact that on the average the temperature of Ewes water is considerably lower than that of Esk or Wauchope, but, of course, the fact remains that salmon do run in Ewes. Would it be because of its lower temperature that the water of Ewes was chosen by the people of Langholm for the drowning of their witches - at a place called the “Grieve” which has never been properly identified but which is popularly supposed to be at its confluence with the Esk. Talking about witches, there is a story told about a minister of Ewes who was greatly annoyed by the too frequent visits to the Manse of one of his elders. The minister tried as nicely as possible to discourage the visits but to no purpose. One night, on the elder going to pay his customary call, he found the minister planting a rowan tree in the Manse garden.

“Oh, no,” said the minister, “I’ve nee bother wi’ the witches, it’s something tee keep elders away I’m wanting.” EWES ROAD The present road up Ewes Valley was constructed under a special Act of Parliament obtained in 1763 by Sir William Pulteney, Laird o£ Westerhall, and was completed some time prior to 1775. Up to the middle of the 18th century the road between Langholm and Hawick was little more than a bridle path, used mainly by pack horses travelling to and from England, hence communication between one town and another was very difficult. In these circumstances there could be but little commerce, and the comparatively small amount of merchandise carried was transported on horseback in creels slung across the animal’s back. The use of pack horses was an absolute necessity, the road being ill-adapted even for them. Between the 17th and 18th centuries, the difficulty of finding any beaten track between Hawick and Langholm is seen from the following extracts taken from the Hawick Burgh records: “1651 . . . Robert Olipher, cordiner, was ardained to pay five pounds to the bailies for disobeying them, by refusing to go and act as guide to the English troopers to Langholm.” “1740 . . . Paid to Thomas Sword for being a guide to the Langholm with an officer of the dragoons, one shilling.” The approach to Ewes in the olden time was from Staplegordon by way of the desolate windings of Sorbie Hass, but on Langholm becoming a separate parish in 1703, the road was by way of the ford crossing at Ewes Foot, a short distance above the junction of the Ewes and Esk, then on towards the Chapel Path, and through the farm lands of Ba’gra to a point near Arkin, where the road came down to the present level. The Ba’gra Road was superseded in 1822 when the present road through Walker’s Hole, and across the Tourneyholm was cut, and the bridge over the Ewes on the site of the High Mill was built. The Miller’s Hill - or Lamb Hill, as it is now called - previous to the cutting of the present road up the Ewes Valley by way of Kilngreen, sloped down to the banks of the river without an obstacle such as hedge or dyke in the way. At that period the Bar Wood was not yet planted. The road to Newcastleton was not yet formed but a road went up the Whitshiells as it now does, and a riding track from the farm house led over the hill-end into Tarras. THE SIMMER FAIR The Simmer Fair - now a thing of the past - was at that time a great event of importance in the neighbourhood. The Miller’s Hill, the Kilngreen and sometimes up to the top of the Castle Hill were on these occasions literally covered with lambs, and buyers and sellers were to be numbered in scores. In his fascinating “Reminiscences,” Simon Irving, of Langholm Mill, states that in his father’s day the ground now occupied by the Langfauld Wood and the Crofts was the Staneholm Farm. This farm extended to the road above Langholm Corn Mill and was broken up by the Duke of Buccleuch when he was approached to grant stints to people in Langholm. PERSONS Another feature which distinguished Ewes was that the clans inhabiting it were different from those in Eskdale. Instead of the Thomsons, Glendinnings, Johnstones, Maxwells and Lindsays, Ewes had Littles, Armstrongs, Elliots, Beatties and Scotts, not the Scotts of Buccleuch but known in history as the “Scotts of Eusdaill” - of the Thirlstane and Howpasley branches. ARMSTRONGS The name of Armstrong and Elliot occurs again and again. Most of the strongholds in the watergate in the 16th and 17th centuries were held by Armstrongs. As early as 1532 Ekke Armstrong occupied a place called Glengillis, and later Will Armstrong, who was a son of Hector of Liddisdale. In 1569 there were still Armstrongs there - who gave assurance for the Scotts of Ewesdale, and their name occurs as late as 1610 in this place. In 1569 Arkilton was occupied by George Armstrong, known as “Ninian’s Geordie” - the Ninian referred to being at Park or Buss where the Armstrongs had been since 1535, and in 1605 Archie Armstrong was in Flaskholm. Sorbie was also in the possession of the Armstrongs and in the Kirkyard is a stone recording the death of John Armstrong of Sorbie, who died in 1685. The lands of Bliss, Howgill and Wrae were also occupied by Armstrongs. Some of these Armstrongs derived from Armstrong of Barnglies who was a kinsman of the famous Johnnie of Gilnockie. There were also Armstrongs in Glendiven, Andrew Armstrong occupying this place in 1643. ELLIOTS The Elliots of Ewesdale were of the Redheuch branch and were ancient allies of the Armstrongs.

In 1578 both upper and nether Fiddleton were occupied by an Elliot as “Will o’ Fiddleton.” At the same time one Ringan - sometimes called Ninian - occupied Ewes Doors, and it indicates a sense of humour among them that he was known as “Ringan the Porter.” We also get Archie Elliot, son to Ringan’s Will, the Proter and Hobbe of Glenvorane was an Elliot. In these descriptions Ewes Doors and Glenvorane seem to refer to the same holding or it was perhaps that Ewes Doors was the “friendly tenant” of Glenvorane, who was a holder of much importance. Everyone has heard of the famous fight between the Elliots and the Scotts in 1566. There had long been a feud between the two clans. The Elliots, led apparently by the Laird of Braidlie, to the number of 400 it is said, concentrated on Ewes Doors as the best strategical position. The battle was a sharp one and many of the Scotts were slain The Armstrongs seem to have occupied Arkleton up to about 1610. By a charter dated 13th June, 1611, the King granted the ten pound lands of Arkilton to William Elliot o£ Fallineske, and I think I am correct in saying that they have remained in the possession of that family since that date, though I believe it is also said that the Arkleton lands came to the Elliots by purchase from the Armstrongs. LITTLES The Littles are the oldest landed or tenant family in Ewesdale. As early as 1426 Simon Little was granted the lands of Meikledale, Sorbie and Kirktoun. There is an interesting stone in the Kirkyard recording the death of Thomas, the Laird’s son, in 1673. The Littles of Langholm are derived from this branch, one of the most influential men in Langholm being Bailie Little whose brother gave the name to the Laird’s Entry. SCOTTS As already stated, the Scotts of Eusdaill were not the Scotts of Buccleuch but of Thirlestane. They were never very influential in Ewes though they contributed to a large extent to the disturbances on the Borders during the 16th century. Someone has said that if you want to learn fully the history of the old Border families, you must search “Pitcairn’s Criminal Trials.” This certainly applies to the Scotts of Ewesdale. Among other exploits they took an active share in Morton’s Raid of Stirling in 1578 also in the Raid of 1585, and several of their names appear in the list of those indemnified: “Thomas Scott of Blackhall and John his son. Adam Scott in Mosspeeble and John his son. John, Geordie and Will Scott and Jock Scott in Arkleton.” The Scotts of Arkleton were not alone in that venture. There were with them the Armstrongs of Howgill, Ekke Armstrong of Gingles and his son, Sam Little of Meikledale, Thomas Armstrong of Wrae, in fact all the Scotts, Armstrongs and Littles of Ewesdale were in the ill-fated expedition. There seems no doubt that they were all ready to take their share in aiding Buccleuch to rescue Kinmont Willie some ten years later. BUCCLEUCH The lands of Ewesdale came finally in 1643 to the Scotts of Buccleuch, excepting those Lairdships which had been granted, such as Arkleton and Meikledale. It should be remembered that when the occupier is also proprietor the designation is “of,” but when it is only a tenancy it is “in,” so we speak of Elliot of Arkleton, Little of Meikledale, Armstrong of Sorbie, but of tenants we say Scotts in Arkleton, Armstrong in Glendiven, Elliots in Ewes Doors and so on, the difference being that the tenants occupied - the “laigh houses” which were an adjunct to the principal. PLACES Ewesdale began to appear in historical documents late in the 13th century and early in the 15th we have reference to the grant of the lands of Meikledale, Kirktoun and Sorbie. Throughout the 16th century there were frequent changes of ownership, lands being granted, “resigned,” and again granted with puzzling frequency, the different owners including Avenels, Frasers, Lindsays, Earls of Mar, Home and Angus, Gideon Murray, Cranstoun, Nithsdale, and finally Buccleuch. It is very interesting to note the recurrence of the same place names again and again. We have: Fiddleton, Blackshaw, Glenvorane (this was probably the most important of all the Ewesdale houses as it possessed the same feudal status as Dumfedling did in Eskdale that of a “free tenandrie,” something lower than a Barony but greater than a mere house), Mosspaul, Mosspeeble, Unthank, Park of Buss, Sorbie, Meikledale, Gingillis, Howgill, Bliss, Flask or Flaskholm, Arkilton, Wrae, Terrona, and Glendiven. These show an Ewesdale very similar in the distribution of places and population to what obtains to-day. These places, remember, were not 20th century bungalows but some of them, such as Glenvorane, Arkleton, and possibly Sorbie, were to some extent fortified houses as the “towers” were usually mentioned as being conveyed with the lands. The name of Park is interesting. From about 1600 there are evidences of a change of name, as it is after that date always referred to as Park of Bus, or Buss, never as Bush. Probably the gradual anglification of our ancient Scots tongue accounts for this last form. Terrona is not mentioned with the same frequency as some of the other houses and its form varies into names hardly recognisable. Apparently it was of less importance then that Flask, which is invariably given as Flask or Flaskholm, which, by the way, is the only occurrence of the Norse “holm” in higher Ewesdale. The lands of Flask are sometimes referred to as extending “even to Terrona,” so it must have been a holding of considerable extent. Sorbie is one of the most interesting places in Ewes. The name occurs with some frequency in Scotland and the north of England indicating the Norse occupation; the “by” or “bie” meaning a habitation. Associated with it is “Sorbie Haas.” “Hass “is Norse for “throat” and when applied to a place means a narrow pass. So far as I am aware its association with the road from Staplegordon and Westerkirk into Ewes is the only use made of the word among local place names. Frequently we get the same name for two places indicated by “Over” and “Nether.” We have the Over-kirk and the Nether Kirk of Ewes Over and Nether Fiddleton, Bliss and Wrae. Unthank is always referred to as Lands: the name is never applied to the Kirk. According to “Place Names of Dumfriesshire,” by Colonel Johnson-Ferguson of Springkell, “the name Unthank denotes a piece of ground on which some squatter settled without leave of the lord.” Arkilton, under many different spellings, frequently occurs after 1530. Gingillis. This is one of the most puzzling places in the watergate. I have no idea what it means but, in the 15th century, it was clearly a place of importance, and incidentally the fount and origin of many of the disturbances which gave Ewesdale a name on the Borders. Meikledale, along with Arkilton, is one of the most famous of all the Houses in Ewesdale and seems to have preserved its identity from the early 15th century. TOWERS When reference is made to such places as “great houses,” I have in mind the references in Charters of the 16th century to the principal house on the lands being conveyed by the charters. For instance, you find granted the lands of Glenvorane “with the tower of Glenvorane to be the principal messuage,” and the lands of Flask and Bliss “with their towers.” But not all of these places can have had strongholds such as we see in what remains of the old Border towers. In Sandison’s Map of the towers of the Debateable Land, dated 1590, the following are given in the watergate of Ewes: Tho of Zingles (shown on the opposite bank of the Ewes, but obviously referring to the same place which was later called Glingillis), Arkleton, Runion o’ the Buss, Hobbe of Glenvorane. At that period such houses were for the greater part built of wood, but some of those in Ewes were certainly of stone - remains having been found up the burn from Meikledale, whilst built into the present Mansion of Arkleton, I am told, are carved stones obviously from a former well-built house or tower, but gone beyond recall are many of the Houses which were influential in Ewesdale 400 years ago. Gone, too, are the days of romance when life on the Borders was an adventure - yes, if you like the days of raiding and reiving. State papers describe our ancestors as the Ewesdale thieves, but remember that the men who called our ancestors thieves were probably themselves deeply implicated in the peculation of public money, for such was then the custom of officialdom. It is quite true that life and conduct on both sides of the Border in the 16th century were not based on the Sermon on the Mount. As well say that our troops who adventured into shell fire and captured German guns and tanks were “stealing” them. The Borders were then in a condition of war and it is mere nonsense to apply to the 16th century a standard of conduct which is only painfully and unsuccessfully attempted in the 20th. KIRKS There were three Kirks to serve the spiritual needs of Ewesdale before the Reformation. Unlike the Kirks of Eskdale, which were under the Abbey of Kelso, the Kirks of Ewes were under the Abbey of Melrose. One was away up in Ewes Doors and was dedicated to St. Paul, and one was at Unthank, though that name is never applied to it in documents. It is invariably referred to as the Over Kirk of Ewes and was dedicated to St. Mark, and the last was at Kirktoun known as the Lower or Nether Kirk of Ewes and was dedicated to St. Cuthbert. We have scarcely any record of the incumbents of the Over Kirk but one parson is mentioned as witnessing a document in the reign of Alexander the Third. There is a fairly reliable record of the ministers of Nether Ewes from the end of the 13th century, but nevertheless the Over Kirk at Unthank appears to be the older foundation. The association of the place name Unthank with the Over Kirk of Ewes is interesting but puzzling. What the precise significance of the name of Unthank is, philologists seem unable to decide but, like that of Cross-Keys, it was generally associated with a religious foundation. The name is found in Cumberland, Durham, and several places in middle England, near Whitby and elsewhere, and its frequency indicates that it had a fairly general application. The Over Kirk of Ewes was abandoned at the Reformation. The watershed of the Esk is quite prolific in such derelict churches. We have also St. Brides, near Westwater, and Wauchope; we have Watcarrick and Byken, in Eskdale, and Staplegordon, which makes six pre-Reformation Kirks abandoned. Of these, Staplegordon, which was under the Priory of Canonbie, was far the most important and famous. The Nether Kirk of Ewes stood on the site of the present building.

Ewes Kirkyard, October 1999

Ewes Kirk as it is today Among its incumbents and ministers were men of distinction whose memories are still honoured in the watergate. One might dwell a considerable time on the merits of John Lithgow, the Covenanter, who was deprived of the living by the Privy Council of 1664, but would not be disloyal to his conscience and so continued to preach in conventicles and had the “honour” of imprisonment on the Bass Rock. Incidentally, one may remark that this same loyalty to Kirk and conscience must have been a characteristic of Ewes folk. There may be some alive still who can remember not a few out of Ewes who, according to their rights, refused to worship in the Established Kirk of Nether Ewes, but walked Sunday after Sunday to the Secession Kirk at the Townhead in Langholm. The late Dr Joseph Brown used to tell a story of a shepherd and his wife, both ardent seceders, who travelled much the same distance. One day the wife went up to the husband who “walked on before” and in awe-struck tones enquired, “John, d’ye ken where the dog’s been ? “No,” said John, “where has it been?” “Weel,” said the wife, “he ran up the steps o’ the Auld Kirk and lookit in at the door.” The couple halted to review the serious situation implied by this announcement, then said Jen, “What maun we dae, Jock?” “I’ll tell ye what,” was the reply, “We can dae nocht the day, seeing its the Sabbath, but we’ll just wait till the morn and we’ll shoot him.” But all the same one must honour the men and women whose inspiring motive was loyalty to their Lord as they conceived their duty, and neither for fear nor favour would be disloyal to their consciences. It was this spirit that made Scotland great among the nations. One could mention, too, and always with pride, the Rev. Robert Malcolm, grandfather of the four Knights of Eskdale. Mr Malcolm was presented to his charge by the Earl of Dalkeith, who also gave him the farm of Burnfoot, formerly named Cannel Shiels, at a nominal rent to help the stipend of Ewes which was at that time very small. Mr Malcolm was the founder of the Poor-house of Ewes. One day the Poor-house was pointed out to an affluent business man from the North of England, who was so impressed with the beauty of its situation and appearance, and the peacefulness of its surroundings, that he asked to have his car stopped in order that he might make enquiries about rooms for his holidays. Then many stories are told of the Rev. Robert Shaw, brother to the Rev. W. B. Shaw of Langholm. Like so many of the old Parish ministers, Mr Shaw had a keen sense of humour and greatly enjoyed a joke. One very cold winter Sunday there was only one occupant of the gallery. Half-way through the sermon the worshippers were amazed to see him rise and address the minister as follows: “It’s awfu’ cauld up here, Mr Shaw, an’ it’ll be nee use bringing Wullie up here wi’ the ladle, so there is ma penny.” He birled the penny towards the pulpit and concluded by saying “Now Aw propose we should sing a psalm and then have the Benediction.” On the occasion of a wedding of someone at the Kirkstyle, the giving in of the names provided a splendid and welcome excuse for some conviviality, and the beadle was despatched to the Manse to crave from the Minister a bottle of whisky wherewith to celebrate the occasion. “Whae’s there?“ asked Mr Shaw. “Oh,” said the beadle, “there’s Jock so-and-so, an’ Wullie so-and-so, an’ Eck so-and-so.” “Oh,” replied the minister, “if Wullie’s there, ye’ll need mair than one bottle. Ye’d better take a couple,” which he handed over to the surprised and gratified official. In a lecture on Ewes given a good many years ago by one Mr James Graham, of Wishaw, he told how the old Kirk was thatched and that people who had brought themselves within the discipline of the Kirk were sent to collect heather and assist in mending the thatch, which strikes one as a very practical way of enjoining and exhibiting repentance. THE BELL The bell, which hangs on one of the trees in the Kirkyard, must be one of the most photographed bells in existence. Regular travellers on the Hawick to Langholm road’ will be familiar with the sight of the old kirk bell fixed in the cleft of an ancient tree in the grounds of the kirk. Unfortunately the tree has had to be cut down owing to its condition. For a very short time the bell found rest in the vestry until another home could be secured for it. Mr Kerr, the minister, has now found the perfect solution by placing the bell in an adjacent tree which provided a suitable cleft. Now the bell is again restored to a tree and this interesting feature of Ewes Kirk is preserved. No doubt you have heard the story of the wedding at Kirkstyle which was so tragically interrupted by the ringing of this self-same bell at dark midnight. Perhaps it might be worth telling again. The fun was getting fast and furious when suddenly there was a toll of the bell. One or two people noticed it, but no one mentioned it and they went on with the dance. Another sharp toll at which womenfolk looked at one another a little scared. The men affected to make light of the incident and the merriment was resumed but in a more chastened spirit. Again came the ominous sound - doubled in number and intensity. This could be ignored no longer. The dancing ceased and the more daring of the men volunteered to venture into the Kirkyard - dead of night though it was - and investigate this mysterious ringing of the bell. Just as they entered, however, there was heard a more clamant toll than ever and the men ran helter-skelter back to the house. Do not blame them, for these were the days of Burke and Hare and everything relating to the Kirkyard was eerie and regarded with fear and superstition. But their being safe in the house did not stop that fearsome ringing of the bell. Consternation reigned and at last the company deemed it an occasion on which the aid of the minister should be invoked. So a deputation set out to the Manse, and, rousing the minister, they told him - what he himself could now hear - how the Kirk bell was being rung by unseen hands whose could be no other than Auld Nick himself. The minister reproved them for their foolish fears and, greatly to their comfort, volunteered to accompany them to ascertain the cause of this unseemly occurrence. They had got to the brig over the Kirktoun Burn when there was another series of loud and insistent peals. They looked to the minister - but he was down on his knees saying “Let us pray” - after which they betook themselves to the wedding. All the long dread night that bell kept ringing and once, when day dawned, there was eager anxiety to ascertain the cause. It was then discovered that someone had maliciously tethered the minister’s goat to the bell rope hanging loose from the tree, and every movement of the goat straining at the tether caused the bell to toll. Great was the indignation at the Kirkstyle, but the culprit was not discovered until many years later, when a well-set-up man visiting his native valley from America, made the astounding confession that he was the scamp who had done this scandalous thing. The Kirkyard contains many interesting memorial stones on which are found the clan names of the Ewes valley and of the neighbouring districts: Littles, Armstrongs, Scotts, Jacksons, Rutherfords, Borthwicks, Beatties, Malcolms, and Aitchisons. On the family stone of the Malcolms appear the names of three of the Knights o£ Eskdale, although, of course, Sir John is not actually buried there. Another stone has the following inscription: “Here lyes Christopher Holiday son to John Holiday who on the 23rd day of December 1747 returning home from Carlisle in company with Adam Graham was on the Beck Moss near Baiting Bush, treacherously assassinated by the said Adam Graham who shot him in the back and with his own staff made 7 wounds in his head and thereafter robbed him. He died of his wounds the day after in the 40th year of his life 1747.” When my attention was drawn to this stone by Mr Slack and I read the inscription, I thought I had discovered an incident which had hitherto escaped all the chroniclers of Langholm and district because, at the first glance, I came to the conclusion that the Beck Moss mentioned on the stone was simply a misspelling and that Becks Moss was really the locus of the crime. However, the murder appears to have been committed in the Longtown district because Baiting Bush is near to Glenzierbank and there is a Beck Moss there, too. While on the subject of stones, one might mention a stone which is placed on the summit of a precipitous slope on the Buss heights. The stone, which I believe has fallen down recently, was placed there to commemorate a daring piece of horsemanship, or, I should say, horsewomanship. The inscription on the stone is as follows: “This stone commemorates Lady Florence Cust’s daring ride straight down this brae with the Eskdale Hounds, 20th February, 1861.” IN SCOTLAND It is curious that both Canonbie and Ewes had to fight for their inclusion in the Kingdom of Scotland. In 1482, the Duke of Albany, uncle of James I, who had granted Meikledale, Sorbie and Kirktoun to Simon Lytel, thought to seize the Scottish Crown, and, in return for English support, he offered to barter away the nationality of this watergate by ceding Ewes to England. In the days when Scottish and English Commissioners were determining the limits of the Debateable Land, the English wardens claimed Canonbie as English. The Canonbie people strongly objected to this and absolutely refused to pay the tribute to England, declaring that they were Scots and had always been Scots, all except Prior John, who claimed Scottish nationality, but at the same time gave assurances to the English warden, like the famous Vicar of Bray. Ewes, too, had a narrow escape, though had the worst then happened, the patriotism of the clans of Ewes would have rectified the blunder of their lord superior. Powerful indeed is the tenacity with which our affections cling to Scotland. It is said that we are blind to its faults - possibly we are. You remember that in one of his whimsicalities, Barrie tells of going to a bookseller’s and asking for a book about Scotland but one which did not always praise Scotland and the Scots but showed their “faults.” The bookseller stared at him and then inquired, “What faults?” The late Ian Maclaren was lecturing once in New York and, at the conclusion of his address, a tall and strapping Highlander was shown into his room and, without for any ceremony, exclaimed: “Man, we’re a wonderful nation.” The lecturer hinted at a few of the national failings, and the Highlander listened to the end and then, waving his hand, he said: “Man, they’re never worth mentioning, never worth mentioning.” And to-day we too are loath to admit them, for Scotland is our home and its men and women are oor ain folk. EWES MEN MATTHEW WELSH I have hinted that Ewes deserves some of the fame attaching to celebrated men of Eskdale - like the Malcolms. But a man may well come within the category of greatness who never won a title or even popular recognition. When I think of the men whom this watergate of Ewes has produced, my mind goes at once to the late Matthew Welsh, a real hero in homespun. On consideration now - remember I was but a boy when Matthew Welsh, an old man, died - I do not think I could -picture a man whom I would take to be so representative of the solid character and intelligence of the Scottish peasantry. Reading the inscription on his tomb, I could not help repeating:

for Matthew Welsh was no mere “mute, inglorious Milton.” I could fancy that it would not be difficult to be a poet if you lived in this beautiful valley, and! Matthew Welsh’s poetic instincts were nurtured on the scenery and the story of the watergate of Ewes. I do not claim that his work will live - who reads Matthew Welsh now-a-days? - nor would I say that his work touched any high mark of poetic expression, but he sang just because he must and his poetry gave much pleasure to those who read it as it did to him in writing it. WILLIAM KNOX It has always been a matter of surprise to me that more value has not been placed locally upon the work of William Knox, at one time tenant of the Wrae. Truly he was not an Ewes man by birth, but I have no doubt that its great natural beauty inspires his muse. His poems are for the most part religious, and one of their defects is the “fleeting scene” outlook they afford of life and destiny. But, apart from this motive, his poem on “Mortality,” written by a young man in his thirties, when optimism ought to be his dominating note, is a piece of very beautiful work viewed from a literary standpoint. As no doubt you know, this poem was a favourite with the great American, Abraham Lincoln, who had it printed and hung in his study, a fact which was urged by those who claimed him wrongly as the author of the poem. HENRY SCOTT RIDDELL But, in thinking of poetry associated with Ewes, one’s mind goes at once to Henry Scott Riddell, born at Sorbie, right in the centre of the watergate. If Henry Scott Riddell had never written another poem other than “Scotland Yet,” this would entitle him to a place in the Temple of Fame. “Scotland’s howes and Scotland’s knowes” - think that phrase is photographic of the valley of Ewes. The song, “Scotland Yet,” is one of the finest songs of patriotism ever penned and amongst Scotsmen, the world over, stands second only to “Auld Lang Syne,” and when we sing it we are proud of the valley of the Ewes which gave it birth. As one thinks of the charming scenery of Ewesdale inspiring poetic expression, it is interesting to speculate as to what would have happened had the railway came up Ewes instead of Liddesdale, as was at one time likely. Possibly Ewes would have become a bungalow town for the man of toil and care in the city crowd of Langholm, but perhaps it is good that the railway has not materialised the valley. Ewes is still rural and pastoral, but had the railway been built we might have had railway sidings on the Flaskholm and a signal box looking into Unthank Kirkyard PRESIDENT ROOSEVELT It is not generally known that the late President Roosevelt had in his veins the blood of a famous Scottish Border family, and a connection with the Ewes valley. Roosevelt was very proud of this connection. In fact he called his favourite terrier “Falla,” after the home of his remote Scottish ancestors, the Murrays of Falla. He is a direct descendent of the “Outlaw Murray,” the hero of a celebrated ballad which was included by Sir Walter Scott in his Minstrelsy of the Scottish Border One of the Murrays became the tenant of the farm of Unthank in Ewes. After settling there he married Barbara Bennet, a daughter of the Laird of Chesters, a small estate near Ancrum. To the union there were born five children of whom James, the eldest, was destined to be the channel for the bringing of the blood of the Outlaw Murray into the Roosevelt family. His father, John Murray, died in 1728, at the early age of 51, leaving his widow and family badly provided for. Four years later, the lease of the farm was taken off the widow’s hands by Walter Scott, an uncle of Sir Walter, and Robert Elliot and her two boys had to begin to make their way in the world. James Murray determined to try his fortune in the New World and in 1735, he embarked for Charleston in South Carolina and ultimately he became a very important personage in the colony. He became involved in the War of Independence and he went to Boston which was occupied by the British troops. When General Howe decided upon its evacuation, Murray sailed to Halifax in Nova Scotia, where he died in 1781. His two daughters had both married supporters of the revolutionary cause. The younger married Edward Hutchison Robbins and their third daughter, christened Anne Jean, married a Joseph Lyman and, a generation later, their daughter, Catherine Robbins Lyman, married a Mr Warren Delano, and one of their children was Sara Delano, who by her marriage to James Roosevelt became the mother of Franklin Delano Roosevelt. There is no broken link in the line of pedigree between the former farmer of Unthank and the late President of the United States, and that forms yet another factor which makes the watergate of Ewes such an interesting place. MOSSPAUL I have purposely left Mosspaul as the last of my references in the watergate. In fact one could give a lecture on the subject of Mosspaul alone, as this famous hostelry comes frequently into the picture of the old coaching days and is full of traditional lore. So far as can be traced, the earliest mention of the Inn is to be found in the autobiographical writing of Dr Carlyle of Inveresk, an eminent personage and one. of the leaders of the church in his day. Travelling towards Langholm, he passed down the Ewes Valley in the year 1767, driving in his open chaise, accompanied by his wife and one or two friends, including the parish minister of Hawick. According to Dr Carlyle, the landlord of Mosspaul at this time was one Rob Achison, but, in contradistinction to this, the late Mr James Edgar, who addressed the members of Hawick Archaeological Society in 1933 on the subject of “Mosspaul and its Historical Associations,” stated that the first landlord of whom any record can be traced was a Thomas Gray, whose name appeared Oil a list in 1803 as one of those who were prepared to defend their country against the threatened French invasion. Probably the most noted visitor to enter Mosspaul was Sir Walter Scott. It was in the autumn of 1792 that Sir Walter, then a young advocate, entered the Ewes Valley for the first time, accompanied by his great friend, Sheriff Shortreed. Previous to this, Scott and his friend, in their search for material for the “Minstrelsy of the Scottish Border,” had visited LiddesdaleóSir Walter’s coach being the first wheeled vehicle ever to be seen in that districtóand they met the famous Willie Elliot of Millburnflat, the original of Dandie Dinmont, who incidentally is supposed to have been buried in Unthank Kirkyard. Further down the Ewes Valley lived old Laird Beattie of Meikledale, who, it is said, supplied Scott with much of his information about Eskdale. Certainly it was Beattie who was responsible for the introduction of Gilpin Homer of Todshawhill into the epic tale of the “Lay of the Last Minstrel.” Other famous visitors to Mosspaul included the poet Wordsworth and his sister Dorothy, while the great statesman William Ewart Gladstone and his wife, in their young days, frequently spent a night at this well known hostelry. The name Mosspaul is understood to be of ancient origin, and it is mentioned in the Charters of the Earl of Home in the beginning of the 16th century but, curiously enough, it is not mentioned in Blaeu’s Map, nor is the Kirk of St. Paul in Ewes Doors. Possibly the most famous landlord of Mosspaul was Robert Govenlock, an uncle of my grandfather, who, coming to Mosspaul in 1816, continued as landlord for 45 years. He was for several years a guard on the mail coach, and was a picturesque figure in his official scarlet coat, top boots and hat trimmed with gold braid. Nine and a half hours were, allowed for the journey of the coach between Edinburgh and Car]isle, the distance being scheduled as 95 miles. After Govenlock, who was familiarly known as “Gloomy Winter,” became landlord, many additions and improvements were made to the hotel but the coming of the railway marked the beginning of the famous inn’s closing days and after 1864 the licence was allowed to lapse. For a number of years the place was occupied as a private dwelling, but afterwards it fell into a ruinous condition. The advent of the cycle created a desire for the resuscitation of Mosspaul and in January, 1900, a company was formed in Hawick and, as a result, the present building was erected and opened on the 7th July, 1900. A crowd numbering several hundreds was present at the ceremony and among the first to drive up to the front door was old Sandy Elder of the Cross Keys, Canonbie, who was at that time 80 years of age, but, nevertheless, he handled the reins of his four-in-hand with the same dexterity as he did when, as a young man, he drove the mail coach up; the self same road. Intimately connected with Mosspaul was the renowned Wisp Club, which took its name from the hill which rises immediately behind the hotel to a highs of 1,950 feet above sea level. The Club, which was composed of the principal farmers in the district, was formed in the spring of 1826, and it was resolved that the members should dine annually in Mosspaul on the Friday after Dumfries Spring Horse Market and record the average prices obtained the previous season for one and two-year-old Galloway cattle, all descriptions of Cheviot and Blackfaced sheep, and their respective wools produced in Scotland south of the Firth of Forth. I might mention one of the resolutions adopted by the Club. This is Rule 2: ”That no person after 1828 will be admitted a member of the Club unless regularly proposed and voted in by two-thirds of the members of the Club present, and that no person will be considered worthy of this Society unless he be able to drink one bottle of whisky.” Amongst the original members of the Wisp Club were two farmers from Ewes: Alexander Pott, Burnfoot, and Robert Scott, Eweslees, and it might also be mentioned that the second landlord of the present hotel when it opened in 1900 was Mr William Allen, now of Charles Street (New), Langholm." |